In 1864, Rebecca Lee Crumpler graduated as a physician from the New England Female Medical College in Boston, the first Black woman to earn that degree in the United States. She went on to care for people through both private practice and government programs and shared her knowledge and compassion with others. Her job, her motive was to “mitigate the affliction of the human race” and to teach others how to do so as well.

Crumpler was born Rebecca Davis on February 8, 1833, to Matilda Webber and Absolum Davis in Delaware. It is unclear why she went to live with an aunt. Her aunt was sought out as a caregiver by the members of her community and was well known for helping her infirm neighbors. Crumpler later credited her aunt with instilling in her a love of medicine. But first Crumpler needed a stronger education, and she attended private schools for a while.

By the late 19th century medicine had been professionalized; you couldn’t just learn as an apprentice or from your family. Women were a minority in medicine and women of color a tiny number even within that minority. Right before professionalism took over, Crumpler learned to care from others from her aunt and from the doctors who allowed her to aid them in their practices from 1852-1860.

Armed with written recommendations, Crumpler was admitted to medical college in 1860 and graduated in four years. The New England Female Medical College in Boston was the first medical college for women in the United States and has a history of nurturing many “firsts” in the field of medicine.

Crumpler was married twice. Her first husband, Wyatt Lee, died from tuberculosis in 1863; they had been married for nearly 11 years. Lee may have been helping her cover the expenses of study, because Crumpler needed the Wade Scholarship Fund to finish her studies the following year; her degree was under the name Rebecca Lee. She opened her first medical practice in Boston that same year.

After the Civil War, Crumpler moved to Richmond to help with the Freedman’s Bureau, and that may be how she met her second husband, Arthur Crumpler. Even though she was working to help Blacks through a Federal program, other physicians and druggists made her life difficult with overt and covert racism and sexism. The couple returned to Boston, where she established a private medical practice in 1869. From all evidence, her practice was a success, even though she helped everyone regardless of their ability to pay. She balanced being a wife, a new mother, and a doctor, but it wasn’t quite enough for her. She had a mission to improve care for everyone.

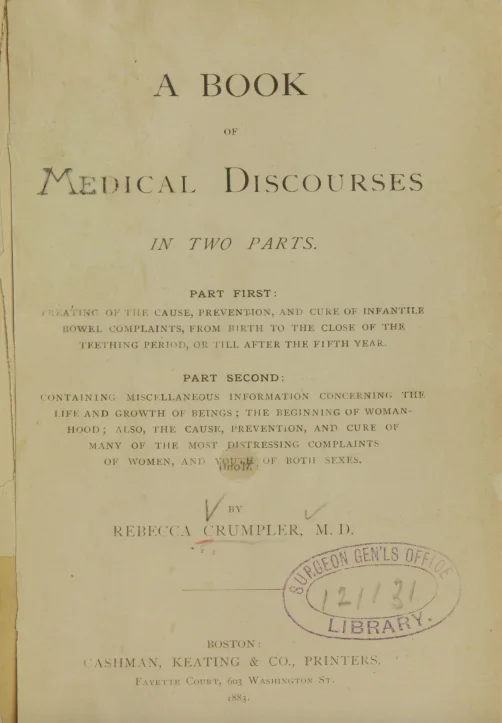

Books were one way to share what you learned with a wider audience. In 1883, “Book of Medical Discources: In Two Parts” (sic) by Rebecca Crumpler, MD, was published. It was one of the first medical books by a Black physician to be published. The contents of the book offered not just physical advice but also social and mental advice for women, from the consideration of marriage through raising a young child. While Crumpler’s target audience was other medical professionals, she explicitly states in the book’s introduction that it is also for women. Think about that for a moment. Imagine how scary it must have been in the late 19th century to get married, be intimate, have a baby, and raise children when by and large women were denied the right to talk or learn about their bodies. Crumpler tried to make those roles understandable, not frightening.

Crumpler may not have realized it, but when she died in 1895, her legacy of placing value on caring for others and education would continue through more than just her books. More than one Rebecca Lee Society was established at institutions of higher learning in Crumpler’s honor. Her place among the important women of America is noted by her home and practice being part of the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail.